Cardiac

Non-Invasive Services

General Clinical Cardiology

You will find healthcare gurus on cardiovascular medicine and interventional cardiology who are best at studying, diagnosing, and treating disorders of the heart and the blood vessels. They use one or a combination of different techniques to identify and treat your heart conditions.

Hypertension

Hypertension is another name for high blood pressure. It can lead to severe health complications and increase the risk of heart disease, stroke, and sometimes death.

Blood pressure is the force that a person’s blood exerts against the walls of their blood vessels. This pressure depends on the resistance of the blood vessels and how hard the heart has to work.

Almost half of all adults in the United States have high blood pressure, but many are not aware of this fact.

Hypertension is a primary risk factor for cardiovascular disease, including stroke, heart attack, heart failure, and aneurysm. Keeping blood pressure under control is vital for preserving health and reducing the risk of these dangerous conditions.

In this article, we explain why blood pressure can increase, how to monitor it, and ways to keep it within a normal range.

Management and treatment

Lifestyle adjustments are the standard, first-line treatment for hypertension. We outline some recommendations here:

Regular physical exercise

Current guidelines recommend that all people, including those with hypertension, engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity, aerobic exercise every week, or 75 minutes a week of high intensity exercise.

People should exercise on at least 5 days of the week.

Examples of suitable activities are walking, jogging, cycling, or swimming.

Stress reduction

Avoiding or learning to manage stress can help a person control blood pressure.

Meditation, warm baths, yoga, and simply going on long walks are relaxation techniques that can help relieve stress.

People should avoid consuming alcohol, recreational drugs, tobacco, and junk food to cope with stress, as these can contribute to elevated blood pressure and the complications of hypertension.

Smoking can increase blood pressure. Avoiding or quitting smoking reduces the risk of hypertension, serious heart conditions, and other health issues.

Medication

People can use specific medications to treat hypertension. Doctors will often recommend a low dose at first. Antihypertensive medications will usually only have minor side effects.

Eventually, people with hypertension will need to combine two or more drugs to manage their blood pressure.

Medications for hypertension include:

- diuretics, including thiazides, chlorthalidone, and indapamide

- beta-blockers and alpha-blockers

- calcium-channel blockers

- central agonists

- peripheral adrenergic inhibitor

- vasodilators

- angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

- angiotensin receptor blockers

The choice of medication depends on the individual and any underlying medical conditions they may experience.

Anyone on antihypertensive medications should carefully read the labels of any over-the-counter (OTC) drugs they may also take, such as decongestants. These OTC drugs may interact with the medications they are taking to lower their blood pressure

Valvular Heart Disease

Valvular heart disease is characterized by damage to or a defect in one of the four heart valves: the mitral, aortic, tricuspid or pulmonary.

The mitral and tricuspid valves control the flow of blood between the atria and the ventricles (the upper and lower chambers of the heart). The pulmonary valve controls the flow of blood from the heart to the lungs, and the aortic valve governs blood flow between the heart and the aorta, and thereby the blood vessels to the rest of the body. The mitral and aortic valves are the ones most frequently affected by valvular heart disease.

Normally functioning valves ensure that blood flows with proper force in the proper direction at the proper time. In valvular heart disease, the valves become too narrow and hardened (stenotic) to open fully, or are unable to close completely (incompetent).

A stenotic valve forces blood to back up in the adjacent heart chamber, while an incompetent valve allows blood to leak back into the chamber it previously exited. To compensate for poor pumping action, the heart muscle enlarges and thickens, thereby losing elasticity and efficiency. In addition, in some cases, blood pooling in the chambers of the heart has a greater tendency to clot, increasing the risk of stroke or pulmonary embolism.

The severity of valvular heart disease varies. In mild cases there may be no symptoms, while in advanced cases, valvular heart disease may lead to congestive heart failure and other complications. Treatment depends upon the extent of the disease.

When to Call an Ambulance

Call an ambulance if you experience severe chest pain.

When to Call Your Doctor

Call your physician if you develop persistent shortness of breath, palpitations or dizziness.

Symptoms

Valve disease symptoms can occur suddenly, depending upon how quickly the disease develops. If it advances slowly, then your heart may adjust and you may not notice the onset of any symptoms easily. Additionally, the severity of the symptoms does not necessarily correlate to the severity of the valve disease. That is, you could have no symptoms at all, but have severe valve disease. Conversely, severe symptoms could arise from even a small valve leak.

Many of the symptoms are similar to those associated with congestive heart failure, such as shortness of breath and wheezing after limited physical exertion and swelling of the feet, ankles, hands or abdomen (edema). Other symptoms include:

- Palpitations, chest pain (may be mild).

- Fatigue.

- Dizziness or fainting (with aortic stenosis).

- Fever (with bacterial endocarditis).

- Rapid weight gain.

Causes

There are many different types of valve disease; some types can be present at birth (congenital), while others may be acquired later in life.

- Heart valve tissue may degenerate with age.

- Rheumatic fever may cause valvular heart disease.

- Bacterial endocarditis, an infection of the inner lining of the heart muscle and heart valves (endocardium), is a cause of valvular heart disease.

- High blood pressure and atherosclerosis may damage the aortic valve.

- A heart attack may damage the muscles that control the heart valves.

- Other disorders such as carcinoid tumors, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or syphilis may damage one or more heart valves.

- Methysergide, a medication used to treat migraine headaches, and some diet drugs may promote valvular heart disease.

- Radiation therapy (used to treat cancer) may be associated with valvular heart disease.

Prevention

Get prompt treatment for a sore throat that lasts longer than 48 hours, especially if accompanied by a fever. Timely administration of antibiotics may prevent the development of rheumatic fever which can cause valvular heart disease.

A heart-healthy lifestyle is also advised to reduce the risks of high blood pressure, atherosclerosis and heart attack.

- Don’t smoke.

- Consume no more than two alcoholic beverages a day.

- Eat a healthy, balanced diet low in salt and fat, exercise regularly and lose weight if you are overweight.

- Adhere to a prescribed treatment program for other forms of heart disease.

- If you are diabetic, maintain careful control of your blood sugar.

Diagnosis

During your examination, the doctor listens for distinctive heart sounds, known as heart murmurs, which indicate valvular heart disease. As part of your diagnosis, you may undergo one or more of the following tests:

- An electrocardiogram, also called an ECG or EKG, to measure the electrical activity of the heart, regularity of heartbeats, thickening of heart muscle (hypertrophy) and heart-muscle damage from coronary artery disease.

- Stress testing, also known as treadmill tests, to measure blood pressure, heart rate, ECG changes and breathing rates during exercise. During this test, the heart’s electrical activity is monitored through small metal sensors applied to your skin while you exercise on a treadmill.

- Chest X-rays.

- Echocardiogram to evaluate heart function. During this test, sound waves bounced off the heart are recorded and translated into images. The pictures can reveal abnormal heart size, shape and movement. Echocardiography also can be used to calculate the ejection fraction, or volume of blood pumped out to the body when the heart contracts.

- Cardiac catheterization, which is the threading of a catheter into the heart chambers to measure pressure irregularities across the valves (to detect stenosis) or to observe backflow of an injected dye on an X-ray (to detect incompetence).

Treatment

The following provides an overview of the treatment options for valvular heart disease:

- Don’t smoke; follow prevention tips for a heart-healthy lifestyle. Avoid excessive alcohol consumption, excessive salt intake and diet pills—all of which may raise blood pressure.

- Your doctor may adopt a “watch and wait” policy for mild or asymptomatic cases.

- A course of antibiotics is prescribed prior to surgery or dental work for those with valvular heart disease, to prevent bacterial endocarditis.

- Long-term antibiotic therapy is recommended to prevent a recurrence of streptococcal infection in those who have had rheumatic fever.

- Antithrombotic (clot-preventing) medications such as aspirin or ticlopidine may be prescribed for those with valvular heart disease who have experienced unexplained transient ischemic attacks, also known as TIAs (see this disorder for more information).

- More potent anticoagulants, such as warfarin, may be prescribed for those who have atrial fibrillation (a common complication of mitral valve disease) or who continue to experience TIAs despite initial treatment. Long-term administration of anticoagulants may be necessary following valve replacement surgery, because prosthetic valves are associated with a higher risk of blood clots.

- Balloon dilatation (a surgical technique involving insertion into a blood vessel of a small balloon that is led via catheter to the narrowed site and then inflated) may be done to widen a stenotic valve.

- Valve Surgery to repair or replace a damaged valve may be necessary.

Replacement valves may be artificial (prosthetic valves) or made from animal tissue (bioprosthetic valves). The type of replacement valve selected depends on the patient’s age, condition, and the specific valve affected.

A number of minimally-invasive cardiac surgeries are performed at the South Arkansas Cardiology. These include:

- Minimally-Invasive Atrial Septal Defect Closure

- Minimally-Invasive Mitral Valve Repair and Replacement

- Minimally-Invasive Aortic Valve Replacement

Cardiac Surgery (Valve Surgery) at South Arkansas Cardiology

What is it? You may have had an illness or injury or been born with a problem that does not let a heart valve work the way it should. You may need to have heart surgery to repair or replace the heart valve.

Why is it necessary?

You have four valves in your heart. Valve surgery is needed when one of the valves in your heart is not working, which means the blood is not flowing through your heart in the right way. Sometimes the valve can be repaired. Other times the valve must be replaced, either with a valve from a pig or one that is manmade.

How is it done?

The surgeon opens the chest by cutting through the breastbone. The surgeon then connects the heart-lung machine. The machine “acts” as the heart and lungs so that the doctor can work on the heart. Once the surgery is done, the heart starts beating and the machine is stopped. The breastbone is wired together to let the bone heal, which takes about four to six weeks.

There are two general areas included in the CVIL: Cardiology and Electrophysiology. The Cardiology section is involved in treating patients with disorders of the heart and vascular tree including coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, valve disease, congenital heart defects, cardiomyopathy and peripheral vascular disease

Arrhythmia

Heart rhythm problems (heart arrhythmias) occur when the electrical impulses that coordinate your heartbeats don’t work properly, causing your heart to beat too fast, too slow or irregularly.

Heart arrhythmias (uh-RITH-me-uhs) may feel like a fluttering or racing heart and may be harmless. However, some heart arrhythmias may cause bothersome — sometimes even life-threatening — signs and symptoms.

Heart arrhythmia treatment can often control or eliminate fast, slow or irregular heartbeats. In addition, because troublesome heart arrhythmias are often made worse — or are even caused — by a weak or damaged heart, you may be able to reduce your arrhythmia risk by adopting a heart-healthy lifestyle.

What’s a normal heartbeat?

Normal heartbeat

Your heart is made up of four chambers — two upper chambers (atria) and two lower chambers (ventricles). Your heart rhythm is normally controlled by a natural pacemaker (sinus node) located in the right atrium. The sinus node produces electrical impulses that normally start each heartbeat. These impulses cause the atria muscles to contract and pump blood into the ventricles.

The electrical impulses then arrive at a cluster of cells called the atrioventricular (AV) node. The AV node slows down the electrical signal before sending it to the ventricles. This slight delay allows the ventricles to fill with blood. When electrical impulses reach the muscles of the ventricles, they contract, causing them to pump blood either to the lungs or to the rest of the body.

In a healthy heart, this process usually goes smoothly, resulting in a normal resting heart rate of 60 to 100 beats a minute.

Types of arrhythmias

Doctors classify arrhythmias not only by where they originate (atria or ventricles) but also by the speed of heart rate they cause:

- Tachycardia: This refers to a fast heartbeat — a resting heart rate greater than 100 beats a minute.

- Bradycardia: This refers to a slow heartbeat — a resting heart rate less than 60 beats a minute.

Not all tachycardias or bradycardias mean you have heart disease. For example, during exercise it’s normal to develop a fast heartbeat as the heart speeds up to provide your tissues with more oxygen-rich blood. During sleep or times of deep relaxation, it’s not unusual for the heartbeat to be slower.

Tachycardias in the atria

Tachycardias originating in the atria include:

- Atrial fibrillation. Atrial fibrillation is a rapid heart rate caused by chaotic electrical impulses in the atria. These signals result in rapid, uncoordinated, weak contractions of the atria.

- The chaotic electrical signals bombard the AV node, usually resulting in an irregular, rapid rhythm of the ventricles. Atrial fibrillation may be temporary, but some episodes won’t end unless treated.

- Atrial fibrillation is associated with serious complications such as stroke.

- Atrial flutter. Atrial flutter is similar to atrial fibrillation. The heartbeats in atrial flutter are more-organized and more-rhythmic electrical impulses than in atrial fibrillation. Atrial flutter may also lead to serious complications such as stroke.

- Supraventricular tachycardia. Supraventricular tachycardia is a broad term that includes many forms of arrhythmia originating above the ventricles (supraventricular) in the atria or AV node. These types of arrhythmia seem to cause sudden episodes of palpitations that begin and end abruptly.

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. In Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, a type of supraventricular tachycardia, there is an extra electrical pathway between the atria and the ventricles, which is present at birth. However, you may not experience symptoms until you’re an adult. This pathway may allow electrical signals to pass between the atria and the ventricles without passing through the AV node, leading to short circuits and rapid heartbeats.

Tachycardias in the ventricles

Tachycardias occurring in the ventricles include:

- Ventricular tachycardia. Ventricular tachycardia is a rapid, regular heart rate that originates with abnormal electrical signals in the ventricles. The rapid heart rate doesn’t allow the ventricles to fill and contract efficiently to pump enough blood to the body. Ventricular tachycardia may not cause serious problems if you have an otherwise healthy heart, but it can be a medical emergency that requires prompt medical treatment if you have heart disease or a weak heart.

- Ventricular fibrillation. Ventricular fibrillation occurs when rapid, chaotic electrical impulses cause the ventricles to quiver ineffectively instead of pumping necessary blood to the body. This serious problem is fatal if the heart isn’t restored to a normal rhythm within minutes.

- Most people who experience ventricular fibrillation have an underlying heart disease or have experienced serious trauma.

- Long QT syndrome. Long QT syndrome is a heart disorder that carries an increased risk of fast, chaotic heartbeats. The rapid heartbeats, caused by changes in the electrical system of your heart, may lead to fainting, and can be life-threatening. In some cases, your heart’s rhythm may be so erratic that it can cause sudden death.

You can be born with a genetic mutation that puts you at risk of long QT syndrome. In addition, several medications may cause long QT syndrome. Some medical conditions, such as congenital heart defects, may also cause long QT syndrome.

Bradycardia — A slow heartbeat

Although a heart rate below 60 beats a minute while at rest is considered bradycardia, a low resting heart rate doesn’t always signal a problem. If you’re physically fit, you may have an efficient heart capable of pumping an adequate supply of blood with fewer than 60 beats a minute at rest.

In addition, certain medications used to treat other conditions, such as high blood pressure, may lower your heart rate. However, if you have a slow heart rate and your heart isn’t pumping enough blood, you may have one of several bradycardias, including:

- Sick sinus syndrome. If your sinus node, which is responsible for setting the pace of your heart, isn’t sending impulses properly, your heart rate may alternate between too slow (bradycardia) and too fast (tachycardia). Sick sinus syndrome can also be caused by scarring near the sinus node that’s slowing, disrupting or blocking the travel of impulses. Sick sinus syndrome is most common among older adults.

- Conduction block. A block of your heart’s electrical pathways can occur in or near the AV node, which lies on the pathway between your atria and your ventricles. A block can also occur along other pathways to each ventricle.

Depending on the location and type of block, the impulses between the upper and lower halves of your heart may be slowed or blocked. If the signal is completely blocked, certain cells in the AV node or ventricles can make a steady, although usually slower, heartbeat.

Some blocks may cause no signs or symptoms, and others may cause skipped beats or bradycardia.

Premature heartbeats

Although it often feels like a skipped heartbeat, a premature heartbeat is actually an extra beat. Even though you may feel an occasional premature beat, it seldom means you have a more serious problem. Still, a premature beat can trigger a longer lasting arrhythmia — especially in people with heart disease. Frequent premature beats that last for several years may lead to a weak heart.

Premature heartbeats may occur when you’re resting or may sometimes be caused by stress, strenuous exercise or stimulants, such as caffeine or nicotine.

Symptoms

Arrhythmias may not cause any signs or symptoms. In fact, your doctor might find you have an arrhythmia before you do, during a routine examination. Noticeable signs and symptoms don’t necessarily mean you have a serious problem, however.

Noticeable arrhythmia symptoms may include:

- A fluttering in your chest

- A racing heartbeat (tachycardia)

- A slow heartbeat (bradycardia)

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath

Other symptoms may include:

- Anxiety

- Fatigue

- Lightheadedness or dizziness

- Sweating

- Fainting (syncope) or near fainting

When to see a doctor

Arrhythmias may cause you to feel premature heartbeats, or you may feel that your heart is racing or beating too slowly. Other signs and symptoms may be related to your heart not pumping effectively due to the fast or slow heartbeat. These include shortness of breath, weakness, dizziness, lightheadedness, fainting or near fainting, and chest pain or discomfort.

Seek urgent medical care if you suddenly or frequently experience any of these signs and symptoms at a time when you wouldn’t expect to feel them.

Ventricular fibrillation is one type of arrhythmia that can be deadly. It occurs when the heart beats with rapid, erratic electrical impulses. This causes the lower chambers in your heart (ventricles) to quiver uselessly instead of pumping blood. Without an effective heartbeat, blood pressure plummets, cutting off blood supply to your vital organs.

A person with ventricular fibrillation will collapse within seconds and soon won’t be breathing or have a pulse. If this occurs, follow these steps:

- Call 911 or the emergency number in your area.

- If there’s no one nearby trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), provide hands-only CPR. That means uninterrupted chest compressions at a rate of 100 to 120 a minute until paramedics arrive. To do chest compressions, push hard and fast in the center of the chest. You don’t need to do rescue breathing.

- If you or someone nearby knows CPR, begin providing it if it’s needed. CPR can help maintain blood flow to the organs until an electrical shock (defibrillation) can be given.

- Find out if an automated external defibrillator (AED) is available nearby. These portable defibrillators, which can deliver an electric shock that may restart heartbeats, are available in an increasing number of places, such as in airplanes, police cars and shopping malls. They can even be purchased for your home.

No training is required. The AED will tell you what to do. It’s programmed to allow a shock only when appropriate.

Causes

Certain conditions can lead to, or cause, an arrhythmia, including:

- A heart attack that’s occurring right now

- Scarring of heart tissue from a prior heart attack

- Changes to your heart’s structure, such as from cardiomyopathy

- Blocked arteries in your heart (coronary artery disease)

- High blood pressure

- Overactive thyroid gland (hyperthyroidism)

- Underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism)

- Diabetes

- Sleep apnea

- Infection with COVID-19

Other things that can cause an arrhythmia include:

- Smoking

- Drinking too much alcohol or caffeine

- Drug abuse

- Stress or anxiety

- Certain medications and supplements, including over-the-counter cold and allergy drugs and nutritional supplements

- Genetics

Risk factors

Certain conditions may increase your risk of developing an arrhythmia. These include:

- Coronary artery disease, other heart problems and previous heart surgery. Narrowed heart arteries, a heart attack, abnormal heart valves, prior heart surgery, heart failure, cardiomyopathy and other heart damage are risk factors for almost any kind of arrhythmia.

- High blood pressure. This increases your risk of developing coronary artery disease. It may also cause the walls of your left ventricle to become stiff and thick, which can change how electrical impulses travel through your heart.

- Congenital heart disease. Being born with a heart abnormality may affect your heart’s rhythm.

- Thyroid problems. Having an overactive or underactive thyroid gland can raise your risk of arrhythmias.

- Diabetes. Your risk of developing coronary artery disease and high blood pressure greatly increases with uncontrolled diabetes.

- Obstructive sleep apnea. This disorder, in which your breathing is interrupted during sleep, can increase your risk of bradycardia, atrial fibrillation and other arrhythmias.

- Electrolyte imbalance. Substances in your blood called electrolytes — such as potassium, sodium, calcium and magnesium — help trigger and conduct the electrical impulses in your heart. Electrolyte levels that are too high or too low can affect your heart’s electrical impulses and contribute to arrhythmia development.

Other factors that may put you at higher risk of developing an arrhythmia include:

- Drugs and supplements. Certain over-the-counter cough and cold medicines and certain prescription drugs may contribute to arrhythmia development.

- Drinking too much alcohol. Drinking too much alcohol can affect the electrical impulses in your heart and can increase the chance of developing atrial fibrillation.

- Caffeine, nicotine or illegal drug use. Caffeine, nicotine and other stimulants can cause your heart to beat faster and may contribute to the development of more-serious arrhythmias. Illegal drugs, such as amphetamines and cocaine, may profoundly affect the heart and lead to many types of arrhythmias or to sudden death due to ventricular fibrillation.

Complications

Certain arrhythmias may increase your risk of developing conditions such as:

- Stroke. Heart arrhythmias are associated with an increased risk of blood clots. If a clot breaks loose, it can travel from your heart to your brain. There it might block blood flow, causing a stroke. If you have a heart arrhythmia, your risk of stroke is increased if you have an existing heart disease or are 65 or older.Certain medications, such as blood thinners, can greatly lower your risk of stroke or damage to other organs caused by blood clots. Your doctor will determine if a blood-thinning medication is appropriate for you, depending on your type of arrhythmia and your risk of blood clots.

- Heart failure. Heart failure can result if your heart is pumping ineffectively for a prolonged period due to a bradycardia or tachycardia, such as atrial fibrillation. Sometimes controlling the rate of an arrhythmia that’s causing heart failure can improve your heart’s function.

Prevention

To prevent heart arrhythmia, it’s important to live a heart-healthy lifestyle to reduce your risk of heart disease. A heart-healthy lifestyle may include:

- Eating a heart-healthy diet

- Staying physically active and keeping a healthy weight

- Avoiding smoking

- Limiting or avoiding caffeine and alcohol

- Reducing stress, as intense stress and anger can cause heart rhythm problems

- Using over-the-counter medications with caution, as some cold and cough medications contain stimulants that may trigger a rapid heartbeat

Congestive Heart Failure (CHF)

Heart failure, sometimes known as congestive heart failure, occurs when your heart muscle doesn’t pump blood as well as it should. Certain conditions, such as narrowed arteries in your heart (coronary artery disease) or high blood pressure, gradually leave your heart too weak or stiff to fill and pump efficiently.

Not all conditions that lead to heart failure can be reversed, but treatments can improve the signs and symptoms of heart failure and help you live longer. Lifestyle changes — such as exercising, reducing sodium in your diet, managing stress, and losing weight — can improve your quality of life.

One way to prevent heart failure is to prevent and control conditions that cause heart failure, such as coronary artery disease, high blood pressure, diabetes or obesity.

Symptoms

Heart failure can be ongoing (chronic), or your condition may start suddenly (acute).

Heart failure signs and symptoms may include:

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea) when you exert yourself or when you lie down

- Fatigue and weakness

- Swelling (edema) in your legs, ankles and feet

- Rapid or irregular heartbeat

- Reduced ability to exercise

- Persistent cough or wheezing with white or pink blood-tinged phlegm

- Increased need to urinate at night

- Swelling of your abdomen (ascites)

- Very rapid weight gain from fluid retention

- Lack of appetite and nausea

- Difficulty concentrating or decreased alertness

- Sudden, severe shortness of breath and coughing up pink, foamy mucus

- Chest pain if your heart failure is caused by a heart attack

When to see a doctor

See your doctor if you think you might be experiencing signs or symptoms of heart failure. Seek emergency treatment if you experience any of the following:

- Chest pain

- Fainting or severe weakness

- Rapid or irregular heartbeat associated with shortness of breath, chest pain or fainting

- Sudden, severe shortness of breath and coughing up pink, foamy mucus

Although these signs and symptoms may be due to heart failure, there are many other possible causes, including other life-threatening heart and lung conditions. Don’t try to diagnose yourself. Call 911 or your local emergency number for immediate help. Emergency room doctors will try to stabilize your condition and determine if your symptoms are due to heart failure or something else.

If you have a diagnosis of heart failure and if any of the symptoms suddenly become worse or you develop a new sign or symptom, it may mean that existing heart failure is getting worse or not responding to treatment. This may be also the case if you gain 5 pounds (2.3 kg) or more within a few days. Contact your doctor promptly.

Causes

Heart failure often develops after other conditions have damaged or weakened your heart. However, the heart doesn’t need to be weakened to cause heart failure. It can also occur if the heart becomes too stiff.

In heart failure, the main pumping chambers of your heart (the ventricles) may become stiff and not fill properly between beats. In some cases of heart failure, your heart muscle may become damaged and weakened, and the ventricles stretch (dilate) to the point that the heart can’t pump blood efficiently throughout your body.

Over time, the heart can no longer keep up with the normal demands placed on it to pump blood to the rest of your body.

An ejection fraction is an important measurement of how well your heart is pumping and is used to help classify heart failure and guide treatment. In a healthy heart, the ejection fraction is 50 percent or higher — meaning that more than half of the blood that fills the ventricle is pumped out with each beat.

But heart failure can occur even with a normal ejection fraction. This happens if the heart muscle becomes stiff from conditions such as high blood pressure.

Heart failure can involve the left side (left ventricle), right side (right ventricle) or both sides of your heart. Generally, heart failure begins with the left side, specifically the left ventricle — your heart’s main pumping chamber.

Type of heart failure

Left-sided heart failure

Fluid may back up in your lungs, causing shortness of breath.

Right-sided heart failure

Fluid may back up into your abdomen, legs and feet, causing swelling.

Systolic heart failure

The left ventricle can’t contract vigorously, indicating a pumping problem.

Diastolic heart failure

(also called heart failure with preserved ejection fraction)

The left ventricle can’t relax or fill fully, indicating a filling problem.

Any of the following conditions can damage or weaken your heart and can cause heart failure. Some of these can be present without your knowing it:

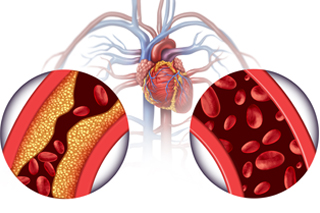

- Coronary artery disease and heart attack. Coronary artery disease is the most common form of heart disease and the most common cause of heart failure. The disease results from the buildup of fatty deposits (plaque) in your arteries, which reduce blood flow and can lead to heart attack.

- High blood pressure (hypertension). If your blood pressure is high, your heart has to work harder than it should to circulate blood throughout your body. Over time, this extra exertion can make your heart muscle too stiff or too weak to effectively pump blood.

- Faulty heart valves. The valves of your heart keep blood flowing in the proper direction through the heart. A damaged valve — due to a heart defect, coronary artery disease or heart infection — forces your heart to work harder, which can weaken it over time.

- Damage to the heart muscle (cardiomyopathy). Heart muscle damage (cardiomyopathy) can have many causes, including several diseases, infections, alcohol abuse and the toxic effect of drugs, such as cocaine or some drugs used for chemotherapy. Genetic factors also can play a role.

- Myocarditis. Myocarditis is an inflammation of the heart muscle. It’s most commonly caused by a virus, including COVID-19, and can lead to left-sided heart failure.

- Heart defects you’re born with (congenital heart defects). If your heart and its chambers or valves haven’t formed correctly, the healthy parts of your heart have to work harder to pump blood through your heart, which, in turn, may lead to heart failure.

- Abnormal heart rhythms (heart arrhythmias). Abnormal heart rhythms may cause your heart to beat too fast, creating extra work for your heart. A slow heartbeat also may lead to heart failure.

- Other diseases. Chronic diseases — such as diabetes, HIV, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, or a buildup of iron (hemochromatosis) or protein (amyloidosis) — also may contribute to heart failure.

Causes of acute heart failure include viruses that attack the heart muscle, severe infections, allergic reactions, blood clots in the lungs, the use of certain medications or any illness that affects the whole body.

Risk factors

A single risk factor may be enough to cause heart failure, but a combination of factors also increases your risk.

Risk factors include:

- High blood pressure. Your heart works harder than it has to if your blood pressure is high.

- Coronary artery disease. Narrowed arteries may limit your heart’s supply of oxygen-rich blood, resulting in weakened heart muscle.

- Heart attack. A heart attack is a form of coronary disease that occurs suddenly. Damage to your heart muscle from a heart attack may mean your heart can no longer pump as well as it should.

- Diabetes. Having diabetes increases your risk of high blood pressure and coronary artery disease.

- Some diabetes medications. The diabetes drugs rosiglitazone (Avandia) and pioglitazone (Actos) have been found to increase the risk of heart failure in some people. Don’t stop taking these medications on your own, though. If you’re taking them, discuss with your doctor whether you need to make any changes.

- Certain medications. Some medications may lead to heart failure or heart problems. Medications that may increase the risk of heart problems include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); certain anesthesia medications; some anti-arrhythmic medications; certain medications used to treat high blood pressure, cancer, blood conditions, neurological conditions, psychiatric conditions, lung conditions, urological conditions, inflammatory conditions and infections; and other prescription and over-the-counter medications.

Don’t stop taking any medications on your own. If you have questions about medications you’re taking, discuss with your doctor whether he or she recommends any changes. - Sleep apnea. The inability to breathe properly while you sleep at night results in low blood oxygen levels and increased risk of abnormal heart rhythms. Both of these problems can weaken the heart.

- Congenital heart defects. Some people who develop heart failure were born with structural heart defects.

- Valvular heart disease. People with valvular heart disease have a higher risk of heart failure.

- Viruses. A viral infection may have damaged your heart muscle.

- Alcohol use. Drinking too much alcohol can weaken heart muscle and lead to heart failure.

- Tobacco use. Using tobacco can increase your risk of heart failure.

- Obesity. People who are obese have a higher risk of developing heart failure.

- Irregular heartbeats. These abnormal rhythms, especially if they are very frequent and fast, can weaken the heart muscle and cause heart failure.

Complications

If you have heart failure, your outlook depends on the cause and the severity, your overall health, and other factors such as your age. Complications can include:

- Kidney damage or failure. Heart failure can reduce the blood flow to your kidneys, which can eventually cause kidney failure if left untreated. Kidney damage from heart failure can require dialysis for treatment.

- Heart valve problems. The valves of your heart, which keep blood flowing in the proper direction through your heart, may not function properly if your heart is enlarged or if the pressure in your heart is very high due to heart failure.

- Heart rhythm problems. Heart rhythm problems (arrhythmias) can be a potential complication of heart failure.

- Liver damage. Heart failure can lead to a buildup of fluid that puts too much pressure on the liver. This fluid backup can lead to scarring, which makes it more difficult for your liver to function properly.

Some people’s symptoms and heart function will improve with proper treatment. However, heart failure can be life-threatening. People with heart failure may have severe symptoms, and some may require heart transplantation or support with a ventricular assist device.

Prevention

The key to preventing heart failure is to reduce your risk factors. You can control or eliminate many of the risk factors for heart disease — high blood pressure and coronary artery disease, for example — by making lifestyle changes along with the help of any needed medications.

Lifestyle changes you can make to help prevent heart failure include:

- Not smoking

- Controlling certain conditions, such as high blood pressure and diabetes

- Staying physically active

- Eating healthy foods

- Maintaining a healthy weight

- Reducing and managing stress

Echo

An echocardiogram uses sound waves to produce images of your heart. This common test allows your doctor to see your heart beating and pumping blood. Your doctor can use the images from an echocardiogram to identify heart disease.

Depending on what information your doctor needs, you may have one of several types of echocardiograms. Each type of echocardiogram involves few, if any, risks.

Why it’s done

Your doctor may suggest an echocardiogram to:

- Check for problems with the valves or chambers of your heart

- Check if heart problems are the cause of symptoms such as shortness of breath or chest pain

- Detect congenital heart defects before birth (fetal echocardiogram)

Type of echocardiogram

The type of echocardiogram you have depends on the information your doctor needs.

Transthoracic echocardiogram

In this standard type of echocardiogram:

- A technician (sonographer) spreads gel on a device (transducer).

- The sonographer presses the transducer firmly against your skin, aiming an ultrasound beam through your chest to your heart.

- The transducer records the sound wave echoes from your heart.

- A computer converts the echoes into moving images on a monitor.

If your lungs or ribs block the view, you may need a small amount of an enhancing agent injected through an intravenous (IV) line. The enhancing agent, which is generally safe and well tolerated, will make your heart’s structures show up more clearly on a monitor.

Transesophageal echocardiogram

If your doctor wants more-detailed images or it’s difficult to get a clear picture of your heart with a standard echocardiogram, your doctor may recommend a transesophageal echocardiogram.

In this procedure:

- Your throat will be numbed, and you’ll be given medications to help you relax.

- A flexible tube containing a transducer is guided down your throat and into the tube connecting your mouth to your stomach (esophagus).

- The transducer records the sound wave echoes from your heart.

- A computer converts the echoes into detailed moving images of your heart, which your doctor can view on a monitor.

Doppler echocardiogram

Sound waves change pitch when they bounce off blood cells moving through your heart and blood vessels. These changes (Doppler signals) can help your doctor measure the speed and direction of the blood flow in your heart.

Doppler techniques are generally used in transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiograms. Doppler techniques can also be used to check blood flow problems and blood pressure in the arteries of your heart — which traditional ultrasound might not detect.

The blood flow shown on the monitor is colorized to help your doctor pinpoint any problems.

Stress echocardiogram

Some heart problems — particularly those involving the arteries that supply blood to your heart muscle (coronary arteries) — occur only during physical activity. Your doctor might recommend a stress echocardiogram to check for coronary artery problems. However, an echocardiogram can’t provide information about any blockages in the heart’s arteries.

In a stress echocardiogram:

- Ultrasound images of your heart are taken before and immediately after you walk on a treadmill or ride a stationary bike

- If you’re unable to exercise, you may get an injection of a medication to make your heart pump as hard as if you were exercising

Risks

No risks are involved in a standard transthoracic echocardiogram. You may feel some discomfort from the transducer being held very firmly against your chest. The firmness is necessary to produce the best images of your heart.

If you have a transesophageal echocardiogram, your throat may be sore for a few hours afterward. Rarely, the tube may scrape the inside of your throat. Your oxygen level will be monitored during the exam to check for any breathing problems caused by sedation medication.

During a stress echocardiogram, exercise or medication — not the echocardiogram itself — may temporarily cause an irregular heartbeat. Serious complications, such as a heart attack, are rare.

How you prepare

Food and medications

No special preparations are necessary for a standard transthoracic echocardiogram. You can eat, drink and take medications as you normally would.

If you’re having a transesophageal echocardiogram, your doctor will ask you not to eat for several hours beforehand.

Other precautions

If you’re having a transesophageal echocardiogram, you won’t be able to drive afterward because of the medication you’ll likely receive. Be sure to arrange for a ride home.

What you can expect

During the procedure

An echocardiogram can be done in the doctor’s office or a hospital.

For a standard transthoracic echocardiogram:

- You’ll undress from the waist up and lie on an examination table or bed.

- The technician will attach sticky patches (electrodes) to your body to help detect and conduct your heart’s electrical currents.

- The technician will also apply a gel to the transducer that improves the conduction of sound waves.

- The technician will move the transducer back and forth over your chest to record images of sound-wave echoes from your heart. You may hear a pulsing “whoosh,” which is the ultrasound recording the blood flowing through your heart.

- You may be asked to breathe in a certain way or to roll onto your left side.

If you have a transesophageal echocardiogram:

- Your throat will be numbed with a spray or gel

- You’ll be given a sedative to help you relax

- The tube containing the transducer will be guided down your throat and into your esophagus, and positioned to obtain images of your heart

Most echocardiograms take less than an hour. If you have a transesophageal echocardiogram, you may be watched for a few hours at the doctor’s office or hospital after the test.

After the procedure

Most people can resume their normal daily activities after an echocardiogram.

If your echocardiogram is normal, no further testing may be needed. If the results are concerning, you may be referred to a doctor trained in heart conditions (cardiologist) for more tests.

Results

Information from the echocardiogram may show:

- Changes in your heart size. Weakened or damaged heart valves, high blood pressure or other diseases can cause the chambers of your heart to enlarge or the walls of your heart to be abnormally thickened.

- Pumping strength. The measurements obtained from an echocardiogram include the percentage of blood that’s pumped out of a filled ventricle with each heartbeat (ejection fraction) and the volume of blood pumped by the heart in one minute (cardiac output). A heart that isn’t pumping enough blood to meet your body’s needs can lead to symptoms of heart failure.

- Damage to the heart muscle. An echocardiogram helps your doctor determine whether all parts of the heart wall are contributing normally to your heart’s pumping activity. Areas of heart wall that move weakly may have been damaged during a heart attack, or be receiving too little oxygen.

- Valve problems. An echocardiogram can help your doctor determine if your heart valves open wide enough for adequate blood flow or close fully to prevent blood leakage.

- Heart defects. An echocardiogram can show problems with the heart chambers, abnormal connections between the heart and major blood vessels, and complex heart defects that are present at birth.

Invasive Services

Right Heart Cath

A right-heart cath with biopsy may be done as part of your evaluation before and after a heart transplant.

Your doctor may do a right-heart catheterization (cath) to see how well or poorly your heart is pumping and to measure the pressures in your heart and lungs. This test is also known as pulmonary artery catheterization.

In a right-heart cath, your doctor guides a special catheter (a small, hollow tube) called a pulmonary artery (PA) catheter to the right side of your heart. He or she then passes the tube into your pulmonary artery. This is the main artery that carries blood to your lungs. Your doctor observes blood flow through your heart and measures the pressures inside your heart and lungs.

As the catheter advances toward your pulmonary artery, your doctor measures pressures along the way, inside the chambers on the right side of your heart. This includes the right atrium and right ventricle. Your doctor can also take indirect measurements of pressures on the left side of your heart. Your cardiac output—the amount of blood your heart pumps per minute—is also determined during a right-heart cath. All of these measurements are used to diagnose heart conditions and to determine what treatment might be right for you.

In some cases, you get intravenous (IV) heart medicine during right-heart cath to see how your heart responds. For example, if the pressure in your pulmonary artery is high, your doctor will give you medicine to dilate, or relax, the blood vessels in your lungs and lower the pressures. A healthcare provider will take several pressure measurements during the procedure to assess your body’s response to the medicines.

If output from your heart is low or the pressures in your heart and lungs are too high, your doctor will leave the PA catheter in place to monitor the effects of different IV medicines. You will most likely be monitored in the intensive care unit (ICU) in this case. This lets your healthcare providers determine the best treatment to improve your heart’s function.

Why might I need a right heart cath?

You might need a right-heart cath to diagnose or manage the following conditions:

- Heart failure. A condition in which your heart muscle has become so weak, it can’t pump blood efficiently. This causes fluid buildup (congestion) in your blood vessels and lungs. Fluid may also buildup in your feet, ankles, and other parts of your body.

- Shock. This causes reduced flow of blood and oxygen to the tissues of your body. Sudden onset of heart failure, severe bacterial infection of your blood stream (sepsis), or severe blood loss (hemorrhagic) can cause shock.

- Congenital heart disease. These are birth defects that develop in the heart. An example is ventricular septal defect. This is a hole in the wall between the lower chambers of your heart.

- Heart valve disease. Malfunction in one or more of your heart valves may interfere with normal blood flow within your heart.

- Cardiomyopathy. This is an enlargement of your heart due to thickening or weakening of your heart muscle. It can eventually lead to heart failure.

- Pulmonary hypertension. Increased pressures in the blood vessels in your lungs. This can lead to trouble breathing and right-sided heart failure.

- Heart transplant. In heart transplant, a right-heart catheterization helps measure the function of the transplanted heart and allows a doctor to take a biopsy to make sure the transplanted heart is not being rejected.

A right-heart cath with biopsy may be done as part of your evaluation before and after a heart transplant. Pressures in your pulmonary (lung) circulation need to be as low as possible for a donor heart to work as well as possible. Excessive pressures will make it hard for the new (donor) heart to pump effectively. A right-heart cath will help to determine if pulmonary pressures can be decreased with medicines (vasodilators) to help ensure a successful transplant. After a heart transplant, the right heart cath with a biopsy measures how well the transplanted heart is working and detects signs of rejection of the transplanted organ.

Your healthcare provider may have other reasons to recommend a right-heart cath with biopsy.

What are the risks of right heart cath?

Possible risks of right-heart cath include:

- Bruising of the skin at the site where the catheter is inserted

- Excessive bleeding because of puncture of the vein during catheter insertion

- Partial collapse of your lung if your neck or chest veins are used to insert the catheter

Other, rare complications may include:

- Abnormal heart rhythms, such as ventricular tachycardia (fast heart rate in your lower heart chambers)

- Cardiac tamponade (fluid buildup around your heart that affects its ability to pump blood effectively), rarely resulting in death

- Low blood pressure

- Infection

- Air embolism (air leaking into your heart or chest area), rarely resulting in death

- Blood clots at the tip of the catheter that can block blood flow

- Pulmonary artery rupture. This is damage to the main artery in your lung. This can result in serious bleeding, making it hard to breathe.

For some people, having to lie still on the cardiac cath table for the length of the procedure may cause some discomfort or back pain.

There may be other risks, depending on your specific condition. Be sure to discuss any concerns with your healthcare provider before the procedure.

How do I get ready for a right heart cath?

Your healthcare provider will explain the procedure and you can ask questions.

- You will be asked to sign a consent form that gives your permission to do the test. Read the form carefully and ask questions if something is not clear.

- Tell your healthcare provider if you are sensitive or allergic to any medicines, latex, tape, or sleep and numbing medicine, or local and general anesthesia.

- If you are pregnant or think you could be, tell your healthcare provider.

- Tell your healthcare provider of all medicines (prescription and over-the-counter) and herbal supplements that you are taking.

- Tell your healthcare provider if you have a history of bleeding disorders, or if you are taking any anticoagulant (blood-thinning) medicines. These may include warfarin, aspirin, or other medicines that affect blood clotting. You may be told to stop some of these medicines before the procedure.

- Tell your healthcare provider if you have a pacemaker or an implantable defibrillator.

- If you have an artificial heart valve, your healthcare provider will decide if you should stop taking warfarin before the procedure.

- You may be asked not to eat or drink anything after midnight, or within 8 hours before the procedure.

- If the insertion site is in your groin, the area around your groin may be shaved.

Left Heart Cath Coronary Angiography

Cardiac catheterization and coronary angiography are minimally invasive methods of studying the heart and the blood vessels that supply the heart (coronary arteries) without doing surgery. These tests are usually done when noninvasive tests do not give sufficient information, when noninvasive tests suggest that there is a heart or blood vessel problem, or when a person has symptoms that make a heart or coronary artery problem very likely. One advantage to these tests is that during the test, doctors can also treat various diseases, including coronary artery disease.

Catheterization of the left side of the heart is done to obtain information about the heart chambers on the left side (left atrium and left ventricle), the mitral valve (located between the left atrium and left ventricle), and the aortic valve (located between the left ventricle and the aorta). The left atrium receives oxygen-rich blood from the lungs, and the left ventricle pumps the blood into the rest of the body. This procedure is usually combined with coronary angiography to obtain information about the coronary arteries.

For catheterization of the left side of the heart, the catheter is inserted into an artery, usually in an arm or the groin.

Cardiac catheterization is used extensively for the diagnosis and treatment of various heart disorders. Cardiac catheterization can be used to measure how much blood the heart pumps out per minute (cardiac output), to detect birth defects of the heart, and to detect and biopsy tumors affecting the heart (for example, a myxoma).

In cardiac catheterization, a thin catheter (a small, flexible, hollow plastic tube) is inserted into an artery or vein in the neck, arm, or groin/upper thigh through a puncture made with a needle. A local anesthetic is given to numb the insertion site. The catheter is then threaded through the major blood vessels and into the chambers of the heart. The procedure is done in the hospital and takes 40 to 60 minutes.

Various small instruments can be advanced through the tube to the tip of the catheter. They include instruments to measure the pressure of blood in each heart chamber and in blood vessels connected to the heart, to view or take ultrasound images of the interior of blood vessels, to take blood samples from different parts of the heart, or to remove a tissue sample from inside the heart for examination under a microscope (biopsy). Common procedures done through the catheter include the following:

-

-

-

- Coronary angiography: A catheter is used to inject a radiopaque contrast agent into the blood vessels that feed the heart (coronary arteries) so that they can be seen on x-rays.

- Ventriculography: A catheter is used to inject a radiopaque contrast agent into one or more heart chambers so that they can be seen on x-rays.

- Valvuloplasty: A catheter is used to widen a narrowed heart valve opening.

- Valve replacement: A catheter is used to replace a valve in the heart without removing the old valve or doing surgery.

-

-

Ventriculography

Ventriculography is a type of angiography in which x-rays are taken as a radiopaque contrast agent is injected into the left or right ventricle of the heart through a catheter. It is done during cardiac catheterization. With this procedure, doctors can see the motion of the left or right ventricle and can thus evaluate the pumping ability of the heart. Based on the heart’s pumping ability, doctors can calculate the ejection fraction (the percentage of blood pumped out by the left ventricle with each heartbeat). Evaluation of the heart’s pumping helps determine how much of the heart has been damaged.

If an artery is used for catheter insertion, the puncture site must be steadily compressed for 10 to 20 minutes after all the instruments are removed. Compression prevents bleeding and bruise formation. However, bleeding occasionally occurs at the puncture site, leaving a large bruise that can persist for weeks but that almost always goes away on its own.

Because inserting a catheter into the heart may cause abnormal heart rhythms, the heart is monitored with electrocardiography (ECG). Usually, doctors can correct an abnormal rhythm by moving the catheter to another position. If this maneuver does not help, the catheter is removed. Very rarely, the heart wall is damaged or punctured when a catheter is inserted, and immediate surgical repair may be required.

Cardiac catheterization may be done on the right or left side of the heart.

Coronary Angiogra

Coronary angiography is seldom uncomfortable and usually takes 30 to 50 minutes. Unless the person is very ill, the person can go home a short time after the procedure. If a stent is placed, the person is usually kept overnight in the hospital.

When the radiopaque contrast agent is injected into the aorta or heart chambers, the person has a temporary feeling of warmth throughout the body as the contrast agent spreads through the bloodstream. The heart rate may increase, and blood pressure may fall slightly. Rarely, the contrast agent causes the heart to slow briefly or even stop. The person may be asked to cough vigorously during the procedure to help correct such problems, which are rarely serious. Rarely, mild complications, such as nausea, vomiting, and coughing, occur.

Serious complications, such as shock, seizures, kidney problems, and sudden cessation of the heart’s pumping (cardiac arrest), are very rare. Side effects of radiopaque contrast agents include allergic reactions and kidney damage. Allergic reactions to the contrast agent range from skin rashes to a rare life-threatening reaction called anaphylaxis. The team doing the procedure is prepared to treat the complications of coronary angiography immediately. Kidney damage almost always goes away on its own. However, doctors are cautious about doing angiography in people who already have impaired kidney function.

Intracoronary PTCA/Stent

Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) is a minimally invasive procedure to open up blocked coronary arteries, allowing blood to circulate unobstructed to the heart muscle.

It is a catheter-based procedure in which a small, expandable balloon and wire mesh tube are inserted into a diseased artery, providing support to hold the artery open. Stents coated with drugs that may help prevent clotting and restenosis have been approved for use in the United States in people with Congestive Heart Disease (CHD). The drugs help fight the tissue and clots that can form inside a stent soon after it has been implanted and promote the growth of smooth arterial tissue over the surface of the stent

Angioplasty and stenting is a catheter-based procedure in which a small, expandable balloon and wire mesh tube is inserted into a diseased artery, providing a support to hold the artery open. Stents coated with drugs that may help prevent clotting and restenosis have been approved for use in the United States in people with Congestive Heart Disease (CHD). The drugs help fight the tissue and clots that can form inside a stent soon after it has been implanted and promote the growth of smooth arterial tissue over the surface of the stent.

HOW DOES IT WORK?

Using a catheter, the coronary artery stent and angioplasty balloon are guided to the site of the narrowed vessel. The balloon is inflated to expand the stent and then removed from the artery. The expanded stents remain in place, keeping the artery open. Tissue will completely grow over it within two to three weeks

WHAT TO EXPECT?

Before the procedure, the physician may order tests including an x-ray, an electrocardiogram, and blood tests.

A physician makes a tiny incision to access an artery in the leg or wrist. Through the incision, a guide wire is inserted in the artery. A short hollow tube (catheter sheath) is then guided over the wire, and then a hollow guide catheter is inserted through the sheath.

Using fluoroscopy (a type of x-ray that projects images onto a monitor), the physician guides the catheter or guide wire through the arterial system to the site where angioplasty is needed. The balloon catheter is passed through the guide catheter or over the guide wire to the point of blockage in the artery and is inflated. The balloon may be deflated and re-inflated until the blockage is flattened and the artery has been adequately opened.

After angioplasty, physicians almost always insert devices called stents to keep the blood vessels open. A tiny, slender, expandable metal-mesh tube, a stent fits inside an artery and acts as scaffolding to prevent the artery from collapsing or being closed by plaque again.

To place a stent, the physician removes the angioplasty balloon catheter and inserts a new catheter on which a closed stent surrounds a deflated balloon. The stent-carrying catheter is advanced through the artery to the site of the blockage. The balloon is inflated, expanding the stent. The balloon is then deflated and the catheter withdrawn, leaving the stent in place permanently.

The patient must remain in bed for 2 to 8 hours following the procedure to allow the access site to heal. During this post-operative period, staff will closely monitor the patient for any complications. The physician may prescribe aspirin or other anti-platelet medications to prevent blood clots. Some patients will go home the same day, and others may need to spend the night. You should make arrangements for both options.

Intracoronary Atherectomy

An atherectomy is a procedure to remove plaque from an artery (blood vessel). Removing plaque makes the artery wider, so blood can flow more freely to the heart muscles. In an atherectomy, the plaque is shaved or vaporized away with tiny rotating blades or a laser on the end of a catheter (a thin, flexible tube).

This procedure is used to treat peripheral artery disease and coronary artery disease. An atherectomy is sometimes performed on patients with a very hard plaque or on patients who have already had angioplasty and stents, but who still have plaque blocking the flow of blood

What is plaque?

Plaque is the build up in arteries of fat, cholesterol, calcium and other substances. When plaque builds, it can block blood flow, or it can rupture, causing blood clots. This build up of plaque is called atherosclerosis. An atherectomy is a treatment for atherosclerosis.

How is an atherectomy performed?

The atherectomy procedure is performed in a cardiac catheterization lab. Before an atherectomy, the patient receives sedatives to help him or her relax. Next, a catheter is gently inserted in an artery, usually in the groin or upper thigh area. It’s then guided through the blood vessel toward the heart. When it’s in place, dye is injected through the catheter and into the coronary arteries. An X-ray is taken to help the physician pinpoint the area that is blocked or narrowed. The physician then uses tiny blades or a laser, attached to the end of the catheter, to cut away or vaporize plaque.

After the atherectomy, an angioplasty or stent procedure is sometimes performed. Once the treatment is complete, the catheter is removed. Most patients go home after about 24 hours.

already had angioplasty and stents, but who still have plaque blocking the flow of blood.

Why choose South Arkansas Cardiovascular and Vein Center for atherectomy.

SARC is a world leader in procedures to re-establish blood flow to the heart. We perform approximately 1,000 interventions per year and offer the latest breakthroughs in the treatment of coronary artery disease including coronary revascularization.

We offer state-of-the-art cardiac catheterization using low-radiation, high-resolution digital equipment that maximizes both patient safety and image quality. Stanford’s three catheterization labs perform more than 4,000 procedures annually.

Transesophageal Echocardiogram (TEE)

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is a test that produces pictures of your heart. TEE uses high-frequency sound waves (ultrasound) to make detailed pictures of your heart and the arteries that lead to and from it. Unlike a standard echocardiogram, the echo transducer that produces the sound waves for TEE is attached to a thin tube that passes through your mouth, down your throat and into your esophagus. Because the esophagus is so close to the upper chambers of the heart, very clear images of those heart structures and valves can be obtained.

Quick facts

-

-

-

- TEE is a test that uses sound waves to make pictures of your heart’s muscle and chambers, valves and outer lining (pericardium), as well as the blood vessels that connect to your heart.

- Doctors often use TEE when they need more detail than a standard echocardiogram can give them.

- The sound waves sent to your heart by the probe in your esophagus are translated into pictures on a video screen.

- After this test, you may have a mild sore throat for a day or two.

-

-

Why do people have TEE?

Doctors use TEE to find problems in your heart’s structure and function. TEE can give clearer pictures of the upper chambers of the heart, and the valves between the upper and lower chambers of the heart, than standard echocardiograms. Doctors may also use TEE if you have a thick chest wall, are obese, have bandages on your chest, or are using a ventilator to help you breathe.

The detailed pictures provided by TEE can help doctors see:

-

-

-

- The size of your heart and how thick its walls are.

- How well your heart is pumping.

- If there is abnormal tissue around your heart valves that could indicate bacterial, viral or fungal infections, or cancer.

- If blood is leaking backward through your heart valves (regurgitation) or if your valves are narrowed or blocked (stenosis).

- If blood clots are in the chambers of your heart, in particular the upper chamber, for example after a stroke.

-

-

TEE is often used to provide information during surgery to repair heart valves, a tear in the aorta or congenital heart lesions. It’s also used during surgical treatment for endocarditis, a bacterial infection of the inner lining of the heart and valves.

What are the risks of TEE?

The few risks of TEE involve passing the probe from your mouth down into your throat and esophagus. You will get medicines before the test to make you calm and to numb your throat. But you may feel like gagging. You may also have a sore throat for a day or two after the test. In very rare cases, TEE causes the esophagus to bleed.

- Category

- Cardiac

- Type of service

- Surgery

- Cost of service

- Starting from $2500